Finding needles of truth in haystacks of fake news

We previously explored, in Aakanksha’s blog, the reasons why people are prone to believe misinformation, and why it might be so difficult for us, psychologically, to attain the truth, despite our best intentions. In this follow-up article I’m going to explore why it’s difficult for us to find the truth from news stories alone, and I’ll share eight top tips for scrutinising the types of academic studies that news stories are often built around.

Part One: Stories change interpretations of truths

Let’s begin with three facts:

- News is big business. Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation has reported profits of more than $500 million in 2021/22.

- People engage with fake news more than fact-based news. Between August 2020 and January 2021, news publishers known for putting out misinformation got more than four times the amount of likes, shares, and interactions on Facebook than ‘trustworthy’ news sources.

- Misinformation spreads faster too. Tweets containing falsehoods are at least 50% more likely to be retweeted than truthful tweets.

So it follows, logically, that news organisations are not incentivised to report the truth. Quite the opposite. And news sources once considered ‘trustworthy’ are increasingly coming under scrutiny. Respected Newsnight presenter Emily Maitlis recently spoke out about bias in the BBC, describing a BBC board member as an “active agent of the Conservative party” who is acting “as the arbiter of BBC impartiality”. Furthermore, a study carried out by researchers at Cardiff University concluded that conservative opinions received more airtime than progressive ones on BBC news coverage.

The reality is, that for as long as facts and quotes are being contrived into a narrative format, they’re being presented with bias. The same facts and quotes can be used to illustrate very different points. For example, here’s an alternative way of framing the same information in the previous paragraph…

…news sources, though considered trustworthy, are increasingly coming under scrutiny. Former Newsnight presenter Emily Maitlis recently accused a BBC board member of being an “active agent of the Conservative party” who is acting “as the arbiter of BBC impartiality”…

In fact there are so many seemingly conflicting studies, that you can pick and choose evidence to reinforce just about any point you’re trying to make, e.g.:

…news sources, though considered trustworthy, are increasingly coming under scrutiny. Former Newsnight presenter Emily Maitlis recently accused a BBC board member of being an “active agent of the Conservative party” who is acting “as the arbiter of BBC impartiality”. This comes despite a 2013 report by the Centre for Policy Studies think tank which concluded that the BBC is biased towards the left…

So how can we possibly know what to believe? My recommendation is to:

- a) read widely, with balance, and with an open (but skeptical) mind. There’s a human inclination to believe the first narrative we hear that makes sense, to seek confirmation of this version of the truth, and filter out or dismiss anything that conflicts with it. Be aware of this and try to catch yourself when you find you’re doing it. And…

- b) find the original source: the interview or academic study, for instance, in its full unfiltered form and original context. And scrutinise it.

Part Two: How to scrutinise research

When scrutinising academic research I’m considering:

1. How was the research study funded?

If there may be a potential conflict of interest, take the research with a pinch of salt.

2. When was the research conducted?

Is it still applicable, or has it been superseded and updated?

3. How many participants were in the study?

Generally speaking: the more, the better. Though this does depend on the type of analysis that’s being done.

4. What demographics do the participants represent?

A lot of studies just use students, for instance. And since different groups of people are motivated by different things, have differing knowledge, skills, financial situations, time constraints, and other influencing contextual factors… results may not be generalisable. Similarly, it can be a certain type of person that volunteers to participate in research, so it’s worth considering whether participants were self-selecting in this way.

5. What stimulus materials were participants exposed to?

Researchers are rarely trained copywriters and designers themselves, and often budgets don’t stretch to allow the enlistment of creative professionals when writing and designing stimulus material and questions for participants. Consider whether stimulus materials illustrate what the author claims they illustrate, or whether prompts/ questions might be open to interpretation or lead participants to answer in a particular way.

6. What research methods were used?

Randomised control trials tend to be the gold standard, as they ensure participant equivalence between groups. It’s also worth considering whether research was conducted in a lab context (controlled, but not always true-to-life) or a real-world context (less controlled, but more true-to-life); whether self-reported behaviour was measured, or actual behaviour (what people say they’ll do isn’t always what they actually do); and whether the study was susceptible to demand effects, e.g. the Hawthorne effect where participants respond differently when being observed.

7. Were the results statistically significant?

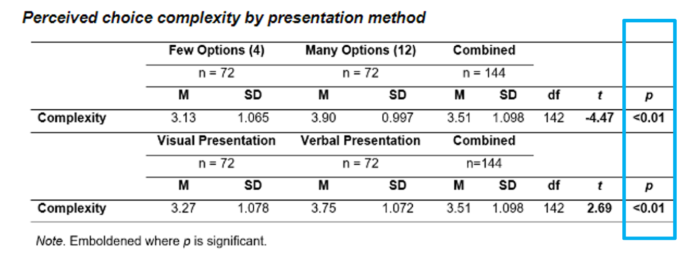

You may encounter tables of results with a column labelled ‘p’. This is their statistical significance. The lower the p value, the more confident you can be that the results are attributable to the defined variables, and not just chance. As a general rule of thumb, if the p value is higher than 0.05, then the results are not worth paying attention to.

8. Has it been replicated?

Have other researchers found the same statistically significant results? Academic success is often judged on ‘Impact factor’, which hinges on number of citations. And there’s often a minimum number of research papers a person in academia is expected to get published per year. In this way, much like the news organisations we were talking about earlier, the systemic structure is headline-driven, incentivises quantity over quality of publication, and often deprives studies with null results from seeing the light of day. If the study you’re looking at hasn’t been replicated, it may be worth checking for it on the Retraction Watch database (www.retractionwatch.com).

In this example, for instance, both p values aren’t just less than 0.05, they’re less than 0.01. Results are therefore worth paying attention to, and you can say with confidence that people found it more complex to choose from a list of 12 options (the mean rating was 3.9 out of 5, where 1 = no complexity at all, and 5 = a great deal of complexity) than a list of 4 (M=3.13); and the same people found it more complex to choose from a verbal list (M=3.75) than a visual list (M=3.27).

Give it a go. Below are the links to the news articles which informed the three facts I led with. My summations were misleading by the way. The actual figures are higher.

- Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation reported profits of $760 million. LINK

- News publishers known for putting out misinformation reportedly got six times the amount of likes, shares, and interactions. LINK

- Tweets containing falsehoods are reportedly 70% more likely to be retweeted than truthful tweets. LINK

And if you want a chat about the importance of accurate information in behaviour change, or anything else, drop me a line at Andrew.Drummond@CorporateCulture.co.uk

Other sources: