What we can learn about human behaviour from how people donate

In this third of a series of blogs sharing findings on big behavioural science topics, behavioural insights specialist Aakanksha Ramkumar looks at key research on how our perceptions of cost influence our willingness to donate to causes.

Reason and emotion

As we move into the third month of the new year, 1.7 years since the Taliban took complete control in Afghanistan, 1 year since Russia invaded Ukraine, and 2 days since the UK announced a plan to permanently refuse asylum for refugees arriving by small boats (amongst a myriad of other calamities) we are, unsurprisingly, seeing rising numbers of refugees across the world. In fact, the global refugee crisis has doubled in the last decade, with over 30 million refugees in 20221.

In light of this, the paper I’ve chosen to focus on this month – Rubaltelli et al: Asymmetric cost and benefit perceptions in willingness‐to‐donate decisions2 – looks at driving donations towards refugee camps. In doing so, it helps us understand how people decide whether to donate or not, and the factors, reasons and emotions at play.

The paper looks at what influences the willingness to make a donation towards a Kenyan refugee camp. It analyses the subjective assessment people make when deciding whether or not to donate. Participants are asked to imagine they have been contacted by a humanitarian aid organisation and are presented with a series of questions which include both the donation costs, and the number of people the donation will help. They are then asked to state whether they will donate or not, how much they feel the donation is a cost to themselves, and how much they feel the donation is a benefit to the recipients.

The results give us a fascinating insight into how people perceive donation requests and process numbers and information. Consequently, the paper implies ways to encourage prosocial behaviour.

Key findings

The paper is split across four different studies. Studies 1 and 2 highlight the importance in understanding the donor’s perception of the costs and benefits of the donation request. Studies 3 and 4 establishes interventions to overcome these perceptions and encourage donations.

Here are the results.

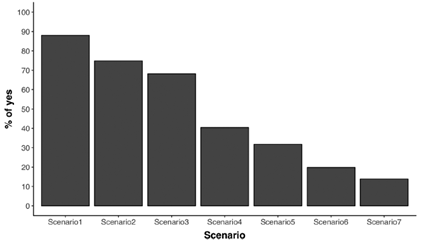

Study 1: As the donation size and number of lives helped increased, participants were less willing to donate. Participants were more sensitive to the cost to themselves, than they were to the benefits for the recipients. In fact, when the costs reached $50 to help 20 children, 60% of participants refused to donate.

Figure 1: Percentage of participants who decided to help in each of the seven hypothetical scenarios of Study 12

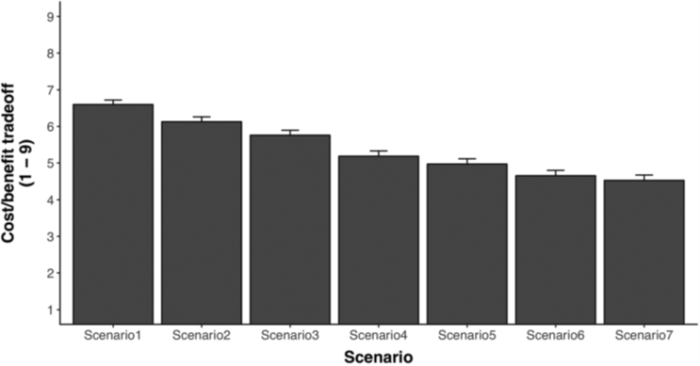

Study 2: They further emphasised how steep cost sensitivity was to participants. As the cost and benefit of helping increased, people began to rate the costs to themselves as more important, and thus were less willing to donate. People need to feel like the costs outweigh the benefits, for them to donate.

Figure 2: Ratings of cost and benefit across the seven hypothetical scenarios of study 22

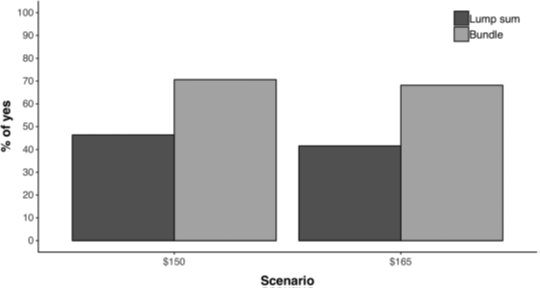

Study 3: Presenting the donation as a bundle of smaller amounts encourages people to make a donation, even when the total amount is larger than what people were willing to donate in the first study. When you present the donation in a bundle, people perceive the costs as lower to themselves than when asked to donate a single sum. Breaking costs into smaller amounts encourages donation.

Figure 3: Percentage of participants who decided to make a donation in each condition of study 32

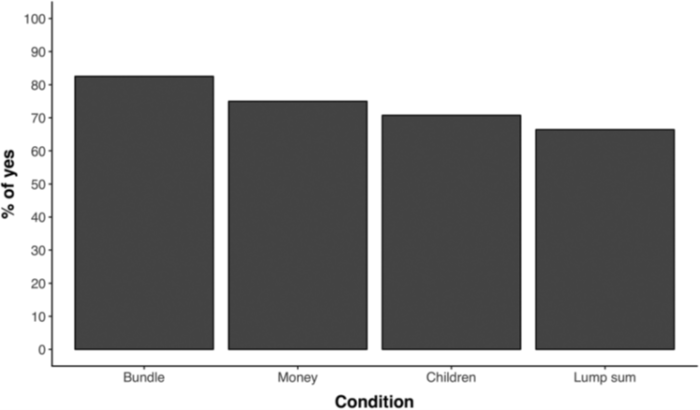

Study 4: Bundling the information helps, and this can be done in a variety of ways; each has different impacts on willingness to donate. The most effective was through bundling different aid programs with the donation amount and how many lives each amount helped. Second was bundling just the costs (without breaking down amount of lives helped with each cost), and in third was bundling just the amount of children helped (without breaking down costs).

Figure 4: Percentage of participants who decided to make a donation in each condition of Study 42

What does this mean?

So, why do people assess the donation costs as outweighing the benefits to the refugees? Why are people less likely to donate when the request is presented as a single figure, but when there are multiple figures, it makes more sense to donate? And why do they feel the costs are lower to themselves when presented as a single donation amount, but when a higher amount is bundled, the costs don’t feel as high?

As surprising as these findings may be, they fall completely in line with a behavioural science concept know as prospect theory3. According to prospect theory, people feel their losses more than their gains. Losing £20 feels worse than winning £20 feels good. So, when the donation amounts are broken into smaller bundles, even with the total amount being relatively higher, the costs don’t feel like a loss.

People’s perceptions are as important, if not more so, than the objective facts and figures. We are only human, after all. Whether a donation amount is high or not, the likelihood of donation depends more on what it feels like to the donor. So, if the benefits feel like they outweigh the costs, people are more likely to donate.

People don’t process information in as straightforward a manner as we might expect. Presenting adequate information in the hopes to change behaviour, is merely a single step in the process. Alongside this, we need to understand the factors that impact behaviour and then develop interventions that convert this understanding into real change.

To discuss how your organisation can leverage a deeper understanding of human nature, or to tackle any behavioural science challenge, just drop me a line at Aakanksha@CorporateCulture.co.uk

References:

- https://www.concern.net/news/largest-refugee-crises

- Paper: Rubaltelli, Enrico, Dorina Hysenbelli, Stephan Dickert, Marcus Mayorga, and Paul Slovic. “Asymmetric cost and benefit perceptions in willingness‐to‐donate decisions.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 33, no. 3 (2020): 304-322.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291. http://doi.org/10.2307/ 1914185