Become an innovator (part 6): Observe with accuracy

This blog series explores the shared characteristics of innovative people and organisations, with a particular focus on what innovators think, feel, believe and do. We’re also looking at how we can all do more to encourage and create innovative workplace cultures.

The sixth of the characteristics shared by all those with a spirit of innovation is: observing with accuracy.

Deduce the details

“Cultivate absolute accuracy in observation, and truthfulness in report…”

Joseph Bell, Scottish physician (1837–1911)

A woman he had never previously met entered the Edinburgh lecture hall of the physician Joseph Bell. She was accompanied by a small child.

“What kind of crossing did you have from Burntisland?” Bell asked.

“It was guid (good),” she replied.

“And had you a guid walk up Inverleith Row?”

“Yes.”

“And what did you do with the other wain (wee one)?”

“I left him with my sister in Leith.”

“And would you still be working at the linoleum factory?”

“Yes.”1

Bell then explained his deductions. The woman had an accent from Fife, just over the Firth of Forth from Edinburgh; the nearest town by the crossing was Burntisland. He noticed red clay on the edges of the soles of her shoes; the only clay of this kind was in Edinburgh’s Botanical Gardens, and the road beside it is Inverleith Row. The coat she carried was too big for the child with her, so she must have left with another child. And the dermatitis on the fingers of her right hand were particular to the workers at the linoleum factory at Burntisland.

Like Joseph Bell (the real life inspiration for Sherlock Holmes), innovators seek out and observe the details. Bell himself put it like this: “Most people see, but do not observe.”

See the difference

- Workarounds: Someone I know in the 1970s used a big stick from her armchair to change TV channels. She was predicting the need for the TV remote.

- What’s missing: Observation includes identifying what’s not there – like the murder weapon at a crime scene.

- Friction: Find the things that get in the way – is it difficult to get your wheelchair on a train?

- Surprises: You want “What the ****!” moments.

The ideas company IDEO also recommends looking for things that prompt behaviour, things people care about, body language and patterns.

There are several skills required here: observing without subjective judgement, articulating what you see (as if others can’t see it), and clearly identifying what you don’t know. You need to be mentally strong enough to step back and articulate what you observe about your own assumptions.

So, what is the difference between seeing and observing?

- Seeing is automatic and involuntary, designed to help us find our way around in the world.

- Observing is seeing consciously and deliberately. Leonardo Da Vinci called this ‘Saper Vedere’ or knowing how to see.

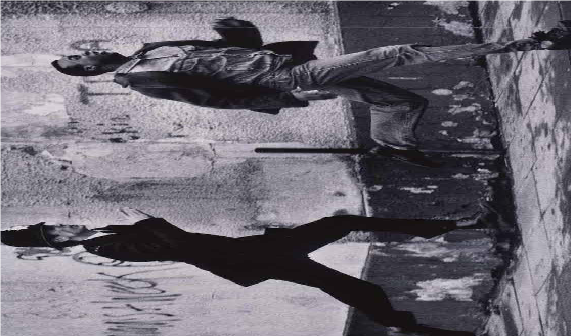

Exercise: Look at this picture…

Now, ask yourself the ‘who, what, where and when’ questions. Say what you see out loud. Then describe what you don’t see and don’t know, because that is usually just as important.

Imagine you are writing a story about the image for a news website. What do you need to know? Again, ask ‘why and how’ questions. Don’t read on until you think you have all the details.

Did you describe what you saw? What were the men wearing? What time of day was it? Who were they? Why were they running? In reality, the picture is from an advert run by London’s Metropolitan Police in 1988. Both men are police officers. One is undercover.2

Innovators observe and absorb with accuracy. They avoid assumption.

Learn more

This is part six of a series of planned articles on the characteristics of innovative people and organisations. The next instalment is coming soon, but in the meantime you can explore the full set in detail, by downloading our free report Innovation for Everyone.

And if you want a chat about how to create a more innovative culture in your organisation, just drop me a line at John.Drummond@CorporateCulture.co.uk

Sources:

- Margalit Fox, ‘Conan Doyle for the Defence’, Profile Books, 2018, p 71/72

- https://www.hatads.org.uk/catalogue/record/a5b4178b-19bf-416f-b765-c73d5b882f10