How do we understand and tackle misinformation?

In this first of a planned series of blogs on the biggest questions and latest findings in behavioural science, behavioural consultant Aakanksha Ramkumar explores misinformation, and how to understand and tackle its powerful grip. The article draws on a review paper on the subject1.

In a world of near infinite data at our fingertips, we’re able to access information much more quickly, and in much higher quantities than ever before. But is more and faster always better? After all, not every piece of information we’re exposed to is from credible, truthful sources.

Alternative facts

Misinformation is defined as information that was presented as true, but later confirmed to be false2. This should not be confused with disinformation, which is deliberately misleading with known false information.

National governments have tackled misinformation in a variety of ways, including: setting up task forces, using law enforcement, legislating with anti-misinformation bills, providing checklists to the public etc. All with varying degrees of success.

But to understand how to counter misinformation, we need to understand how people are evaluating information in the first place.

Evaluating truth

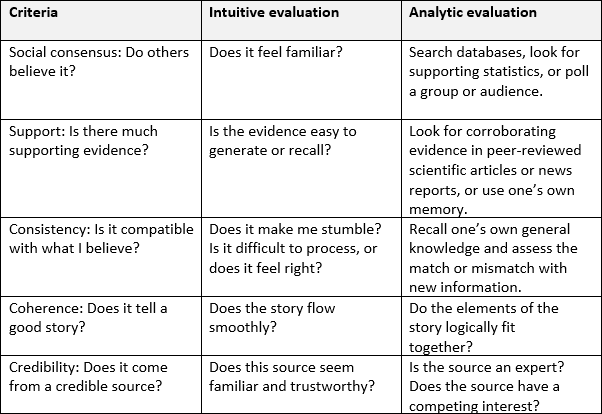

People evaluate the truth by focusing on specific criteria. In doing so, they ask at least one of these kinds of questions: Who else thinks this is true? Is there evidence? Is this compatible with my beliefs? Does it make sense, or tell a coherent story? Is the source trustworthy?3

These questions cover a wide variety of areas that are sensible to look into when trying to evaluate information. However, the way people think, and the susceptibility of our memory, means that we won’t always arrive at the same answers to the same question, especially at times when the truth is unclear. In such circumstances, we become more inclined to rely on our mental heuristics and unconscious biases, because we are making decisions under uncertainty. This is something I discuss in depth in a previous article.

The people we look to as experts, those around us we trust, our belief systems and attitudes, and our personal intuition also all play a part in the way we seek truth, and remember information.

Expecting people to analytically evaluate information they come across is unrealistic. We are exposed to massive amounts of data daily, and proper analysis would be time consuming and laborious. Instead, people often rely on a more intuitive approach, so-called “fluent processing”4, which is quicker and easier.

The differences between intuitive and analytical evaluation are shown below.

Table: Five criteria people use for judging truth1

Influencing factors

There are a number of other factors that have been shown to influence our understanding of the truth, including:

- The more times we hear something, the more familiar and, therefore, believable it becomes2. The impact is similar, whether we hear the same thing several times from a single person, or the same total number of times, but from several people5. This can make the myth-vs-fact strategy backfire3.

- If information is difficult to remember, we feel that there is less evidence. However, if we can retrieve the information easily, we feel there is more evidence to substantiate the claim6. To tackle this, we need to find ways to frame the truth in ways that are easier to grasp and more memorable.

- Information that forms a coherent story is easier for people to make sense of, and thus become more likely to believe as truth7. This makes complex or non-linear information difficult to process and accept.

- When it comes to credible sources, we’re more likely to believe someone if we can pronounce their name easily8 or if they have an accent that is native to us9, further underscoring the power of familiarity.

- Anecdotes10, photos11 and rhymes12 all make information easier to remember, and are tools that can be used to engage and persuade readers.

Just the facts

We can see how difficult it might be to attain the truth despite our best intentions, due to the myriad of factors that impact our analysis, understanding and memory. When information feels easy to understand and remember, we’re more likely to believe it and spend less time analysing the credibility of it. Consequently, information that is difficult to understand and unfamiliar might increase the need to dive further into its validity.

The key takeaway from this review is that ‘repetition increases acceptance’. Therefore, it’s important to ignore the myths and instead focus only on elevating and repeating the facts.

To discuss how your organisation can help tackle misinformation, or any behavioural science challenge, just drop me a line at Aakanksha.Ramkumar@Choiceology.co.uk

References:

- Schwarz, N., Newman, E., & Leach, W. (2016). Making the truth stick & the myths fade: Lessons from cognitive psychology. Behavioral Science & Policy, 2(1), 85-95

- Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13, 106–131

- Schwarz, N. (2015). Metacognition. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, E. Borgida, & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology: Attitudes and social cognition (Vol. 1, pp. 203–229). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Reber, R., & Schwarz, N. (1999). Effects of perceptual fluency on judgments of truth. Consciousness and Cognition, 8, 338–342

- Weaver, K., Garcia, S. M., Schwarz, N., & Miller, D. T. (2007). Inferring the popularity of an opinion from its familiarity: A repetitive voice can sound like a chorus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 821–833.

- Schwarz, N., Sanna, L. J., Skurnik, I., & Yoon, C. (2007). Metacognitive experiences and the intricacies of setting people straight: Implications for debiasing and public information campaigns. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 127–161.

- Johnson-Laird, P. N. (2012). Inference with mental models. In K. Holyoak & R. G. Morrison (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 134–145). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Newman, E. J., Sanson, M., Miller, E. K., Quigley-McBride, A., Foster, J. L., Bernstein, D. M., & Garry, M. (2014). People with easier to pronounce names promote truthiness of claims. PloS One, 9(2), Article e88671. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088671

- Lev-Ari, S., & Keysar, B. (2010). Why don’t we believe non-native speakers? The influence of accent on credibility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 1093–1096.

- Fagerlin, A., Wang, C., & Ubel, P. A. (2005). Reducing the influence of anecdotal reasoning on people’s health care decisions: Is a picture worth a thousand statistics? Medical Decision Making, 25, 398–405.

- Newman, E. J., Garry, M., Bernstein, D. M., Kantner, J., & Lindsay, D. S. (2012). Nonprobative photographs (or words) inflate truthiness. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19, 969–974.

- McGlone, M. S., & Tofighbakhsh, J. (2000). Birds of a feather flock conjointly (?): Rhyme as reason in aphorisms. Psychological Science, 11, 424–428.