The state of water in the UK 2022

This is a blog of two halves – problems and solutions. Consider it a provocation. It leads into our annual roundtable on the state of water in the UK, taking place on 9th November 2022. To reserve your place at the roundtable and find out more head here.

Part one: Troubled water

The water sector in the UK is in deep water.

Scientists say the summer 2022 drought in Europe could prove to be the worst in 500 years. By the end of August, drought was declared across 11 of England’s 14 Environment Agency areas. An all-time high temperature of 40 degrees Celsius was recorded in England in July. Only 14% of rivers in England are in good ecological health. Heavy rain, when it comes, could cause flash floods. Sea water rises over the next 30 years are highly likely to change the coast of the UK.

Impacts to water have a wide ripple. Less water, of course, affects what’s available to us to drink, to shower, to keep our gardens green and our cars clean. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Drought also means less water for irrigation and lower crop yields, which drives up prices. Water is used in energy generation and the production of products. Heatwaves increase pressure on the NHS. If water in the UK is in crisis, then so is energy, food, health and the economy.

Damned leakage

The first issue to come up during a drought is leakage. The daily demand for water in England and Wales is 14bn litres. However, more than 2bn litres are lost daily to leaks. Clearly, fixing them could make a massive dent in heading off a drought.

So, are the water companies making progress? Yes. In England, leaks fell fastest between 1994 and 2000. They reduced by a third. They have come down another 8% since then. In Scotland, leaks have more than halved in the last 16 years. But is it enough, and what’s the plan for the future?

Earlier this year, the water sector in England launched “A Leakage Routemap to 2050” through trade organisation Water UK. The ambition is to reduce current losses of water by a third by 2030 and halve water leakage based on 2018 levels by 2050. My guess is that any ambition in this space is all but invisible to customers.

Dirty water

In November 2021, the Environment Agency and Ofwat launched a criminal investigation into 2,200 sewage treatment works in England after concerns that discharges were not complying with permits.

Earlier this month (October 2022) OFWAT fined 11 of the water companies a total of £150m for missing targets relating to water supply and sewage flooding. Also this month, the new Environment Secretary announced his intention to massively increased civil penalties for water companies who pollute the environment – up from £250k to £250m.

A sour taste

All of this gives the media the opportunity it wants to contrast the companies’ track records with dividends and executive pay. Water companies have paid out £57bn in dividends to investors since privatisation 30 years ago.

The highest pay for a water sector CEO in 2020 was close to £4m, compared to the FTSE 100 average CEO salary of £2.7m. Can it be justified to pay any water company CEO, operating in a near monopoly, more than the average FTSE 100 business?

Trust and the communications void

The result of this brew of issues are renewed calls for the water sector to be renationalised. That’s not going to happen for two reasons. It’s not affordable. And there is no political will. It won’t happen under the Tories, and Keir Starmer ruled it out this month for the opposition.

But it reveals a deep distrust in the sector. And this deep distrust is directly proportionate to the failure of the sector to invest in communications. Customers, citizens and consumers are unaware of the real value of water. They are unaware of the immediate risks of flooding or drought on their local communities. They are unprepared for the growing risk of extreme weather events. They are unaware of the trade-offs required to protect their future.

There is another massive communications void. We have no knowledge of the water companies’ perspective on the public policy options to secure the future of water.

The lack of political will

The government could choose to massively increase investment in the sector – perhaps as part of its new growth agenda. The government may say this is already happening. They would refer to the new Storm Overflows Discharge Plan with proposed investment by the water sector of £56bn over 25 years. If we add in investment to fix all water infrastructure, the cost grows again substantially. We also need to understand that there is a cyclical nature to infrastructure investment and that it’s close to 30 years since the massive investment in the 1990s.

There have to be question marks over political will for massive capital investment against other priorities. For example, school infrastructure is crumbling and needs another £13bn for urgent repairs. The NHS is falling apart with a record 6.6m waiting for treatment. Remember, this is a governing party that has reduced the annual grant to the Environment Agency from £120m in 2010 to £40m. Environment doesn’t seem to be a major priority. And remember, the reason the water sector was privatised in the first place was to help address the chronic underfunding in the sector.

Who pays?

The cost of investment is met by customer bills and by investors. The new Storm Overflow Plan suggests increases in customer bills to help fund the increased investment.

What about investors? Ofwat, on its website is clear, dividends are the cost of borrowing money from investors in order to invest to improve the water network. These investors, by the way, are often not the caricatures we have of rapacious financial organisations. They are often pension funds protecting the future of ordinary workers. Ofwat says dividends to shareholders are “to avoid customers’ bills increasing drastically”.

One way or another citizens pay. “If you want greater resilience to drought, then you have to increase water bills or general taxation,” said Sir John Armitt, chair of the National Infrastructure Commission in a recent interview with the Guardian.

But once again, there is a communications gap. The water companies don’t make the case to customers and citizens of the trade-offs. And the investors remain faceless.

Flaws in regulation

Here’s the way the system is supposed to work. Defra defines its priorities for the regulator. The directions to Ofwat this year sound good. “Ofwat should challenge the water industry to plan, invest in, and operate its water and wastewater services to secure the needs of current and future customers, in a way which delivers value to customers, the environment and wider society over the long-term.”

Ofwat tells the water companies how they should put their plans together for the next five-year period. The water companies consult their customers and put in recommendations that are likely to have the support of customers. Ofwat makes a decision.

That’s how it should work. Here’s how it’s likely to work…

The water companies consult their customers via a thorough and deep process. Customers give their views, and say, as they have done before, that they are happy to pay more for a resilient network. The plans are submitted to Ofwat. But there is low political will to raise prices, especially during a cost-of-living crisis. Radical change is therefore unlikely, meaning more drought, more flooding, and more media opprobrium. And it is communities that suffer. Again.

Dangerous brew

Together all these issues make a potent and dangerous brew. Drought. Flooding. Leakage. Sewer discharges. High executive salaries. Private ownership. Dividends. Rising prices. Lack of political will. Flawed regulation. Low public awareness of the issues. Low trust. Lack of communications. Lack of vision.

There are solutions. But what are they? And are the main actors likely to act?

Part two: The bridge

There are actions water companies can take to build a bridge over these troubled waters. Below are seven of them; all that’s needed is the will to act.

One: bridge the knowledge gap on the value of water

The obvious starting point is for the sector to communicate the true value of water. We have, together, singularly failed to communicate the value of water beyond supplying clean water to homes and taking away dirty water.

Water is essential for food, critical for energy generation, required for producing cars, phones and other products, essential for tourism and for eating out. A lack of water hits the economy, effects health and is essential for plant life which generates the oxygen we need to live. Water shortages are likely to increase involuntary migration, drive social unrest and may even lead to conflict.

Two: bridge the information gap on immediate risks

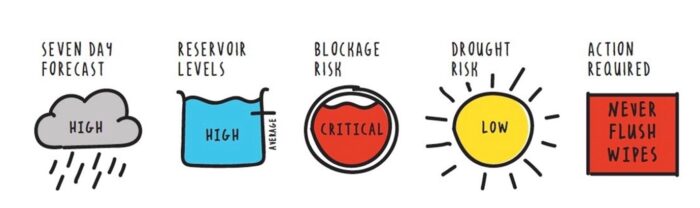

We need continuous, daily information to individuals and communities on the immediate risks – not just during times of extreme weather. This information should be as readily available as weather forecasts or travel reports. This kind of thing:

Three: bridge the vision gap

Define a vision for water in the UK. The water companies must have a powerful visible vision for the future of water. Citizens and communities need to know the value of water, the risks to water and how the water sector intends to address those risks.

What needs to be done? By when? By whom? How will it be funded? What are the alternatives? What is needed by politicians, regulators, other companies, communities and citizens to bring the vision to life? Why would the sector fail to lead?

Four: bridge the regulatory gap

Do our regulators need to be reformed? Are they acting in the best long-term interests of citizens? The Environment Agency gets it. A year ago, presumably frustrated by lack of government action and funding, they urged us to “adapt or die”.

Less than a year ago, the House of Lords published a report on government preparation for extreme risks. It recommended an Office for Preparedness and Resilience. “It’s extraordinary that the National Risk Register does not get any public promotion or media coverage,” said Professor David Spiegelhalter of Cambridge University. “These vital issues deserve to be widely known and discussed.”

It’s time for the water sector – and every other organisation dependent on a resilient water sector – to create a manifesto demanding public policy change.

Five: bridge the behaviour change gap

The sector needs to become more effective at delivering behaviour change at scale. Current efforts are not enough. Behaviour change is a discipline. The 2022 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said demand-side action could address between 40% and 70% of CO2 emissions. Consumer action alone can massively reduce daily demand for water and massively reduce pollution incidents. Why is it still not being adopted at scale by the sector?

Here are some other linked thoughts: communications directors should be on the Board; one of the directors should be named as a chief context officer to monitor major relevant contextual issues; best practice and research insight should be widely shared; cross-sector campaigns should be run with the energy and food sectors; core campaign resources should be created for use by others; and while the water sector can lead, it does not solely own action.

Six: bridge the gap in community resilience

If the government and regulators won’t take the lead, water companies need to act to help communities prepare for extreme weather events. Drought, flooding and heatwaves all have an impact on community wellbeing. Communities need the skills, organisation and processes to respond. There is surely a compelling case for the water sector to lead. The British Red Cross has a resilience index measuring community vulnerability and capacity by local authority area.

Seven: define and break down barriers

There are barriers to building the bridge. They are likely to include a desire to meet shareholder expectations, a desire to exceed the performance of other water companies, and reluctance to invest in communications. Others include:

- Plan continuity bias: All the water companies are required to produce a drought plan every five years. Each plan has triggers for different levels of action, such as dry weather or drought. But if pre-set thresholds aren’t met, no action is triggered. Sticking to the plan can be high risk.

- Independence: The structure of the sector means the companies are largely focused on their own region (only 4% of water supplies are transferred between companies). The problem is that there are dependencies across regions and across sectors, such that the impact of drought in one area (e.g., a major crop producer) can hit the population in others.

- Reputational concern: Water companies prefer to avoid upsetting customers and the media by imposing restrictions on water use. Yet there are greater reputational upsides from telling customers exactly the state of resources and encouraging personal action.

We are in deep water. A resilient future for water should concern us all. But there are solutions. All we need is the will to act.

If you’d like to talk about the resilience of water, or any other resource, just drop me a line at John.Drummond@CorporateCulture.co.uk

John Drummond is Chairman of Corporate Culture Group. He has worked with Ofwat, Thames Water, Anglian Water, Southern Water, Yorkshire Water and Scottish Water, and is a former Group Communications Director with United Utilities.