Why good people ignore bad things: 3 lessons from behavioural science

In this second of a series of blogs sharing findings on big behavioural science topics, behavioural insights specialist Aakanksha Ramkumar looks at key research on closing the gap between our intentions and our actions.

Choosing to act

The field of behavioural science has helped underpin some of our big questions around human behaviour. One of which is explaining the intention-action gap. This occurs when someone fully wants and intends to do something (e.g., exercise more, use their phone less, recycle… and so on) but ultimately, they don’t act.

Human behaviour is complex, and with each situation there can be a myriad of unique reasons as to why peoples’ intentions don’t always convert to action. In this article, I’m focusing on how the way we process information can make us ignore human suffering, from Paul Slovic’s 2010 paper: If I look at the mass, I will never act: Psychic numbing and genocide1.

Daniel Kahneman2 famously presented the theory of the dual processing system, which helps us make decisions. System 1 processing is quick, reactive, intuitive, and emotional, while system 2 is slower, more reasoned, and logical. While they are characteristically different, a common myth is that they work autonomously. In reality, they rely on one another.

Affective response

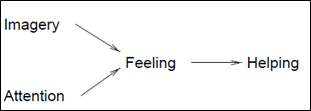

Reacting to negative events, such as genocide, and then being moved to do something about it, is linked to what’s called affective response, which primarily sits within system 1. When we experience an emotion, we might be moved into action because “without affect, information lacks meaning”. So, it’s necessary to invoke feelings to motivate action, which in this case is helping behaviour – see figure 1.

Figure 1: Imagery and attention produce feelings that motivate helping behaviour1.

However, negative feelings are unpleasant, and what happens most often is that “they motivate actions and thoughts to avoid these feelings”. The origins of system 1 developed to protect small human communities from immediate danger, which explains why paying attention to distant large-scale calamites goes against the way our brains are wired.

The paper presents a small exercise by Annie Dillard3 to help us understand the boundaries of the human mind when trying to comprehend large numbers. She asks, “There are 1,198,500,000 people alive now in China. To get a feel for what this means, simply take yourself — in all your singularity, importance, complexity, and love — and multiply by 1,198,500,000. See? Nothing to it.” It feels impossible.

Lesson 1: Our ‘affective responses’ are powerful, but very limited.

Psychic numbing4

As the exercise above shows, we are not capable of processing the scale of humanity. This then also prevents us from being able to empathise with the pain and suffering being experienced by large groups of people.

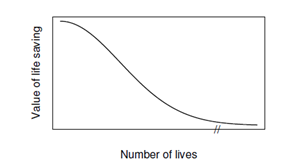

Slovic’s paper goes on to explain how the way we process information goes against us in a way. For example, when there is a steady increase in stimulus, it induces a smaller and smaller response.

So, for calamities that are steadily getting worse (through loss of lives, say), our response doesn’t increase in magnitude with it but instead wears down. Think of any negative events that are not in decline but are steadily getting worse. There is an initial peak in response but over time this gradually fades away and we become less willing to help as the scale increases. See figure 2.

Figure 2: A model depicting psychic numbing – the collapse of compassion – when valuing the saving of lives1.

Lesson 2: An increase in the magnitude of a disaster does not imply a proportionate increase in response, it might actually do the opposite.

Create empathy

So how do we get people to understand the scale of impact? The paper details several experiments that show us what works and what doesn’t.

For example, portraying loss of life in mere numbers doesn’t get the message across, but presenting them as proportions does. To the point where an experiment showed that college students favoured saving a high percentage of lives, over students asked to save a whole number of lives5. This is because it is easier to evaluate: the higher the proportion the better we feel.

Additionally, the more of a narrative we build by providing information that makes the victims ‘identifiable’ the more it encourages helpful behaviour. We are much more willing to help people that we know something about, than when they are presented as a statistic.

Lesson 3: Numbers don’t create powerful affective responses on their own, instead we need a mix of numbers, a story, and compelling images.

Generate objectivity

As stated in Slovic’s paper, system 1 will always be highly impacted by stimulus that generates strong feelings, such as compelling images and powerful stories. Several behavioural science-led solutions focus on circumventing the errors that system 1 is naturally prone to.

These kinds of solutions can be powerful and often cost-effective, but Slovic proposes instead to encourage system 2 to play a stronger role. This would make the call to action less dependent on the subjectivity of how one feels at that moment in time, but instead generate a more poignant objectivity on the loss of lives and what it means for humanity.

The paper also doesn’t shy away from pointing out that as much as understanding “the collapse of compassion” and generating public empathy is important, there is a significant role to be played by politics and international law that can’t be ignored.

To discuss how your organisation can close the intention-action gap of your stakeholders, or to tackle any behavioural science challenge, just drop me a line at aakanksha@corporateculture.co.uk

References:

- Slovic, P. (2010). If I look at the mass, I will never act: Psychic numbing and genocide. In Emotions and risky technologies (pp. 37-59). Springer, Dordrecht.

- Kahneman, D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality. American Psychologist, 58, 697–720.

- Dillard, A. (1999). For the time being. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Lifton, R. J. (1967). Death in life: Survivors of Hiroshima. New York: Random House.

- Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2004). Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Analysis, 24, 1–12.